Aziz Abu Sarah and Maoz Inon: Building the Road to Peace

On Sunday, September 28, the halfway mark between Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, I attended a talk in Manhattan featuring peace activists Aziz Abu Sarah and Maoz Inon.

This ten-day period, known as “The Days of Awe,” is when Jews are called upon to engage in self-examination, renewal, reflection on their actions over the past twelve months, and to repair the damage they have caused to others. The timing was perfect to hear these men share their stories and vision for the peaceful future of Palestine and Israel.

The Brotherhood Synagogue in Gramercy Park, led by Rabbi Daniel Alder, hosted the event. It is a temple I know well, as it is the congregation where my son had his Bar Mitzvah.

On-site early, I had the opportunity to speak with Maoz and Aziz before attendees arrived. After offering my condolences to Maoz on the death of his parents on October 7, we talked about the current despair and violence gripping the land.

“We need to go back to the Judaism of our prophets,” Maoz told me. “The opposite of what Israel is now. We can’t wait for the prophets. Where is Shalom?”

Maoz acknowledged that Israelis were traumatized, but emphasized that public opinion was flexible. “Our role is to envision a new reality, and talk about the future.” He underscored, “We’re speaking about values, not terms.” He paused and then continued. “I know about human life. It’s sacred. Each of us should be accountable. [We need to] bring this potential for the scenario to happen. A wall will never protect us.” He said definitively, “By 2030, there will be peace.”

When I spoke to Aziz, we delved into the divisions between and among both Palestinians and Israelis. “There will always be extremists,” he said. “You sideline them and create an alternative.”

The meeting room filled up quickly by 2 p.m. Rabbi Amichai Lau-Lavie, founder of Lab/Shul, and Rabbi Jill Jacobs of T’ruah spoke briefly to the crowd. Jacobs mentioned the silent vigil that had taken place in front of the United Nations, where protestors had held up photos of hostages remaining in Gaza and Palestinian children who the Israeli military had killed. “We have to break down the dichotomy,” she said, “to a both/and.” They announced the weekly Union Square meeting later that afternoon, organized by Israelis for Peace and NYC Friends of Standing Together, which would also feature Maoz and Aziz.

Rabbi Margo Hughes-Robinson, the Executive Director of Partners for Progressive Israel, was the moderator. Together, as co-presidents of InterAct (whose joint work has included a meeting with Pope Leo XIV in May 2025), Aziz explained, “Before we start, we set expectations. We give each other a hug.”

Maoz began. “Aziz and I have been doing this work for the past two years. The situation is going from worse to worse. The old order and reality are broken. If there are not new ways, there will be a crash.” He then said, “My reality was broken on October 7. My parents lived close to the border for thirty years.” Maoz related how he had spoken to his father early that morning. There seemed to be some kind of escalation on the perimeter. Maoz went to make his coffee after signing off the call with, “Talk to you soon.” Then, news trickled in. Maoz learned that Hamas was in the community. His calls to his parents got no response. At 4 p.m., he and his siblings were able to reach neighbors of his parents, who notified him that the house had been “burned to ashes, with two bodies inside.”

Maoz’s family began to sit shiva. The family agreed to reject the “cycle of blood and revenge that has been happening for years.” Through his grief and tears, Maoz had a vision of humanity where the blood on the land would be “washed clean” from all the crying. When Maoz awoke, he resolved to heal himself by choosing a different path.

A message from the universe came in the form of a call from Aziz, whom Maoz had met a decade earlier through their work in the tourism industry. The person who had introduced them had contacted Aziz to inform him of Maoz’s loss. Aziz’s reaction to that horrific day was, “What has been done is an act of cowards.”

At this point, Aziz picked up the thread of connection to share his narrative. “I reached out because I’ve been in that space,” he said.

“I’ve experienced the Occupation since I was a little kid. I was seven years old during the Intifada.” Aziz described his desire to stay home from school because of the constant tear gas from Israeli soldiers he would experience on his walk to attend classes. His mother insisted that he go, giving him freshly cut onions to mitigate the chemical irritants. Two years later, his brother was arrested and taken to prison for throwing stones at the IDF. While incarcerated, his brother was tortured and died shortly after his release. Now, at ten years old, without preparation for a flood of overwhelming anger and vengeance, Aziz had to find a way to continue his life.

For the next eight years, Aziz was politically active. He realized that if he wanted to go to college, he would need to learn Hebrew. He enrolled in an Ulpan course and joined a group comprised of Jewish immigrants. He was afraid, thinking that everyone would hate him. However, the breakthrough moment came when his teacher greeted him in Arabic. Aziz said, “I had never experienced an Israeli who treated me nicely. My story of transformation started in that classroom.”

Aziz reflected on all his friends from Gaza who have lost innumerable family members and acquaintances. He speculated that if he took an inventory of everyone he knew who had perished, it would reach 1,000 people. “How do we use our passion and anger?” Aziz asked rhetorically. “Peace is impossible because we have not desired it enough.”

After drilling down on their personal stories, Rabbi Hughes-Robinson thanked them for “the gift you have given to the audience.”

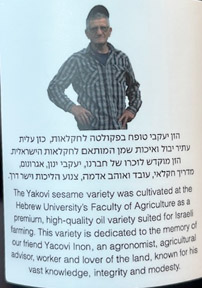

Maoz spoke about his father as an example of creating and envisioning a goal. He said, “My father was the best farmer in Israel.” Maoz recounted the story of the sesame oil his father had cultivated from various and specific seeds to create a superior blended product. “My father taught me by action. He was a farmer for fifty-eight years. His team always analyzed their formula and what they had done the previous season. What could they do better?” What was the best strategy to develop and refine the outcome?

Transitioning to the issue of peace building, Maoz said, “We want to sow the seeds of the future. We want to dream, build coalitions, create a road map, and execute the plan.” He quoted Psalm 126:5. “Those who sow in tears will reap with joy.”

The conversation moved easily between Maoz and Aziz, who expressed, “We have to prepare ourselves for the next season.” He commented on a peace gathering held in 2024 that had 6,000 participants. In May of 2025, they had 10,000 participants in Jerusalem. “Groups have to work together,” underscored Aziz. Through their InterAct organization, “legitimization is the key.” Aziz pointed out that “until now, no negotiations have included peace makers.” The need to engage those in a range of fields, from faith leaders to politicians, was reinforced.

It is their shared backgrounds in travel and tourism, along with the lessons learned, that give them insights off the beaten track. Aziz detailed his efforts to revitalize Nazareth, the cultural capital of Palestinians in Israel. The city’s demographics are primarily comprised of Nakba refugees and their descendants. Mazon discussed the guest house he had opened in Nazareth in 2005. Like Aziz, he has also traveled to the world’s hotspots and learned about indigenous cultures. He said, “At 30, I realized I had been living inside the walls of ignorance.” To the crowd, he stressed, “Let’s leave the past and present behind and focus on values.”

“Don’t divide us,” intoned Aziz. “If you do, make it between believers of peace values and those not there yet.”

Aziz was definitive in his criticism of American, Israeli, and Palestinian media, which filter stories through their respective lenses. He addressed the shortcomings of Palestinian leadership. “We have to work harder to amplify the work of peace initiatives. It’s up to us. With challenge comes innovation.”

The response to audience questions centered on two themes: peace is possible, and mobilizing those who are already convinced of that, while finding common ground through shared values. The power of “civil society” was a foremost point for Aziz. He stated, “Indifference is the worst enemy.” The premise of never underestimating the power of the individual was also prominent. On a pragmatic basis, Aziz urged the American public, “Stop sending billions in weapons and invest in peace. We need to treat war like a disease and [that] those working to end it are looking for a vaccine.”

Maoz noted that he was looking forward to reading the story of Jonah during the Yom Kippur Mincha services. The prophet’s tale is featured during the holiday because of its concepts of repentance, compassion for all, and the ability for individuals and groups to change and evolve.

As Maoz said, “All of our dreams can be fulfilled if we have the courage to pursue them.”

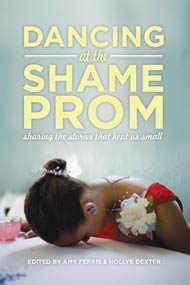

“The Future Is Peace: A Shared Journey Across the Holy Land,” written by Aziz and Maoz, is scheduled for publication in April 2026 and is now available for pre-order.

Photos: Marcia G. Yerman