A Conversation with Freddy Rodríguez

Every life has events of consequence. Those happenings impact and direct the future flow of consciousness. Sometimes, the ramifications remain beneath the surface. In other circumstances, the thread is easy to recognize. If you are an artist, such as Freddy Rodríguez, it manifests in your work.

Rodríguez was born in the Dominican Republic in 1945. He came from a family of artists. His granduncle was Yoryi Morel, one of the founders of Dominican modernism. Creating art as a child, Rodríguez made masks for carnival from paper and starch. While attending a private elementary school, Rodríguez began drawing maps, where he won competitions for his efforts. By 14, he was regularly acknowledged in his geography class for his “best” achievements. One such example was his “octopus in an ocean.” Even then, Rodríguez didn’t want art to “imitate reality.” Rather, he aspired to have the viewing be magical. He told me, “I make art to have people experience something new.”

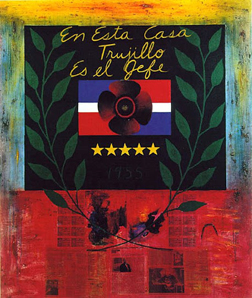

Yet there was nothing magical about living under the rule of a dictator, and the history of Rodríguez’s country of birth permeates his oeuvre.

The Dominican Republic was discovered by Columbus, which led the way to waves of European imperialism that would follow. In the first decade of the 1500s, slaves were imported. By 1522, the first slave uprising in the Americas occurred. The island was subject to various power brokers. The Catholic Church sought influence among the populace. The United States occupied the country for eight years commencing in 1916. In 1930, strongman Rafael Trujillo took the reins of power. Known globally for his brutality, his mark on the island was obliterated in 1961 when he was ambushed and killed.

In the immediate post-Trujillo years, Rodríguez was part of an “improvised” political student movement for freedom in the Dominican Republic. “The kind of freedom that is denied in a dictatorship,” he said. Word got to him— through channels from those in government—that he “needed to leave.” As he related, “Friends were tortured and killed. Things were very bad.”

Rodríguez came to the United States in 1963 at the age of 18. Though totally alone, he completed his high school degree. A teacher gave him free passes to the Museum of Modern Art. It was an experience that he was unused to—as there were no museums in his country. He frequented the Museum of Natural History, calling it “a revelation.” He sketched at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and went to galleries “religiously.”

The loss of Rodríguez’s mother in 1964, while he was in the United States, was compounded by the fact that he was “very close to her.” He said, “I never saw her again and that changed my life.” As a new legal resident of the country facing the draft in 1966, Rodríguez headed back to the Dominican Republic. He then lived briefly in Puerto Rico, where he worked for a steamship company before returning to New York City.

Discussing his early years with me, Rodríguez’s narrative was laced with the realities of the challenges he faced as a person of color. “I lived here because I had no choice—but I was not treated well in the 1960s. When I came to this country, a label was put on me—and it wasn’t positive.”

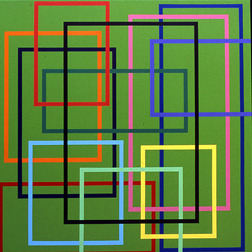

When Rodríguez resettled in Manhattan, he enrolled at the Fashion Institute of Technology and the New School for Social Research. “At that time,” Rodríguez said, ”you didn’t need money to be an artist.” In 1969, he reconnected with artist pal Ed Taylor, who was making textiles. Rodríguez saw that it would be “great training.” He said, “It was very rigorous. There were perimeters. It taught me how to work with limitations. Color theory was vital.” At the New School, Rodríguez studied with Carmen Cicero, who at the time was doing geometric painting. Beyond the technicalities of art-making, they conversed about art history, literature, and the works of other artists. It was in Cicero’s class that Rodríguez executed his first hard-edged painting, using the process of laying down tape.

While describing the trajectory of his work, Rodríguez segued into a commentary on the gallery scene and the “business of art.” He said, “The art market is so segregated it is unbelievable. How can a Dominican enter that world?” He continued, “A lot of critics are ignorant of culture and content. Carmen Herrera was doing geometric painting in the 1940s. Criticism is from the European perspective. It’s also who you are and who you know.” Yet Rodríguez maintained that despite the obstacles, he was his only competition. “I compete with myself, and hope that the next one [painting] is better,” he stated.

As an artist who prides himself on continual exploration, Rodríguez also pointed to the galleries and critics who had a problem with the fluidity with which he changed techniques and stylistic approaches. “I don’t like to repeat myself,” he emphasized. His output is prodigious, and his method of creating is rapid. As an aside to potential detractors he noted, “A person is constantly growing and changing, which is influenced by their life…unless they’re one-dimensional.”

Rodríguez’s attraction to abstract art began with his appreciation of the discipline and primary colors of Piet Mondrian. In Mark Rothko, he connected with the emotional qualities inherent in the canvases. Rodríguez saw Frank Stella as a “kindred spirit, an artist constantly challenging himself to do new things.”

With a touch of irony, Rodríguez pointed out how “those in the art world were somewhat surprised by his works that dealt purely with abstraction. They don’t associate abstraction with Caribbean art.” He observed wryly, “We can’t think in the abstract?”

This very point was addressed in the exhibit, Our America: The Latino Presence in American Art, at the Smithsonian American Art Museum. A multi-themed presentation, Rodríguez is represented with the group of artists, “Defying Categories.” He has three works from 1974 included. Each acrylic on canvas is a narrow vertical, measuring 96″ x 32″. They exemplify Rodríguez’s use of geometry and color to animate the picture plane.

Despite barriers, Rodríguez racked up numerous solo exhibits, nationally and globally, and has been the recipient of many fellowships and awards. He received a Joan Mitchell Foundation Grant, was a Gregory Millard Fellow in Painting, and served as a New York State Council for the Arts Artist in Residence at El Museo del Barrio—an experience he reflected on with great satisfaction. Rodríguez has work owned by the Bronx Museum, the Queens Museum, el Museo del Barrio, the Newark Museum, the Smithsonian American Art Museum, and the Museo de Las Casas Reales in Santo Domingo. Corporations such as American Express and Smith Barney have included him in their collections. Recently, he was selected to be in the pilot phase of the CALL program (Creating a Living Legacy), which helps artists to properly document and archive their work and career.

Rodríguez was chosen to design the prestigious memorial to Flight 587. Speaking about his approach to the project, he said, “I used my knowledge of art and my minimalist background. My memorial is filled with all kinds of symbols and metaphors. It also deals with the immigrant experience, religious life, and the occurrence of death. There is a gate. People go back and forth—like the gates of paradise. The openings in the memorial, the cut-outs, they allow light to come through. It is for remembrance. The souls of the dead are captured by the light. For those who are visiting, the memorial functions on many levels. In its simplicity, there is spirituality.”

After speaking with Rodríguez extensively in the living room of his home in Queens, New York (not far from where assemblage master Joseph Cornell lived), we went to his studio. Housed in a separate structure on his property, it held racks of paintings, works in progress, a table Rodríguez uses to work horizontally when pouring paint, and sculptures propped against the walls. There was plenty to look at, and Rodríguez spoke enthusiastically about each piece.

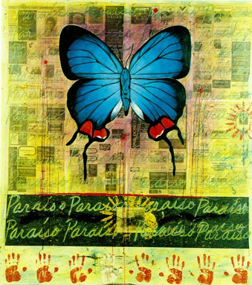

“You have to be so alert for the kind of work I do,” Rodríguez said. “All my work has some kind of a conceptual meaning behind it. I do think a lot.” When we first connected, Rodríguez immediately discussed his affinity and admiration for the renowned Argentine writer Julio Cortázar—who was also a political activist. Words as imagery and as contextual material are integral to much of Rodríguez’s output. This is evident in his collage on canvas series, where phrases are juxtaposed with symbolic icons on a backdrop of surfaces that include newspaper, fabric, and found materials. In Paradise for a Tourist Brochure, Rodríguez implements one of his visual stand-ins, butterflies, for the people and country of the Dominican Republic. With the word “paraíso,” which translates to paradise or heaven, he presents viewers with a different side of the lush island culture that tourists expect to experience.

More accurately, the tiny red circles with drip marks read as bullet holes, and the handprints serve as bloody reminders of those who have died from political violence under the iron hand of repression.

In Rodríguez’s most recent project, finished in late 2013, he has combined text and painting in the form of a one-of-a-kind book. He has given it the appellation, Mi Joda, which he translates as, To Upset the System. Here, he has incorporated his own words in a relationship with his painting.

Rodríguez said, “I think it’s my job to keep exploring and learning new things. This was overtly apparent in his studio as I viewed sculptures; images that encompassed responses to the tsunami that destroyed Japan; his endeavor to “transform baseball stats to the visual realm; folding screens.

Included in the blockbuster show Caribbean: Crossroads of the World, termed “the big art event of the summer season in New York” by Holland Cotter in his New York Times review, Rodríguez’s piece Homage to Tony Peña is also featured in the companion book. The show will be viewed at a series of museums and in conjunction with a full schedule of programs. It’s currently on view at the Pérez Art Museum Miami.

Through the wide range of work that Rodríguez shared with me, and the personal history that he had narrated, his final statement summed up the whole visit:

“My truth is in my art.”

This article is from the series “Evolution of an Artist”

Photos courtesy of Freddy Rodríguez

6 Responses

[…] was in power, and after his assassination in 1961 a period of chaos enveloped the country. In a 2014 interview with the artist and curator Marcia G. Yerman, Mr. Rodríguez said he was involved in a student […]

[…] was in power, and after his assassination in 1961 a period of chaos enveloped the country. In a 2014 interview with the artist and curator Marcia G. Yerman, Mr. Rodríguez said he was involved in a student […]

[…] was in power, and after his assassination in 1961 a period of chaos enveloped the country. In a 2014 interview with the artist and curator Marcia G. Yerman, Mr. Rodríguez said he was involved in a student […]

[…] was in power, and after his assassination in 1961 a period of chaos enveloped the country. In a 2014 interview with the artist and curator Marcia G. Yerman, Mr. Rodríguez said he was involved in a student […]

[…] was in power, and after his assassination in 1961 a period of chaos enveloped the country. In a 2014 interview with the artist and curator Marcia G. Yerman, Mr. Rodríguez said he was involved in a student […]

[…] was in power, and after his assassination in 1961 a period of chaos enveloped the country. In a 2014 interview with the artist and curator Marcia G. Yerman, Mr. Rodríguez said he was involved in a student […]