A Conversation with Grace Graupe-Pillard

In a refurbished synagogue in Keyport, New Jersey, Grace Graupe-Pillard works virtually non-stop creating art. The format varies—paintings, video, drawing, and photography—yet all are integral to her vision. Perhaps it is ironic that her workspace was previously home to an Orthodox Jewish congregation. Although Graupe-Pillard is adamant that she is an atheist, her sensibility is very much informed by the consciousness that came with having German refugee parents—and relatives that perished in the Nazi death camps. Her work is infused with the concerns of the outsider, the downtrodden, the marginalized, and the oppressed. War, social justice, and a call for an acknowledgement of the world’s ills permeate her material.

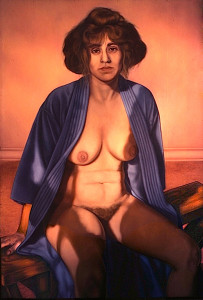

Graupe-Pillard also has a flip side that is funny, mischievous, and feisty. It is evidenced as she cavorts unabashedly naked through everyday scenarios in the archival pigment prints that comprise her I Can Still Dance images, or when she is redefining and poking fun at art history in Grace Delving Into Art. In the oil painting grouping, Self-Portrait as A Blonde, Graupe-Pillard overturns feminine stereotypes, while simultaneously kicking the precedence of the “male gaze,” sexism, and ageism squarely in the rear.

Crouching Grace As A Blonde

2014

Oil/Alkyd/Wood

60” x 48″

Growing up as a twin in Washington Heights, New York City, Graupe-Pillard was surrounded by free-floating anxiety and whispered conversations about family members who had disappeared in Germany. (Her paternal grandparents were killed in Theresienstadt.) Her father was an architect. Her mother—who had hoped to be a doctor—was a dressmaker. It wasn’t until decades later that Graupe-Pillard would come to fully appreciate her mother’s creativity.

Accepted into the Music and Art High School, Graupe-Pillard entered a world in the middle of Manhattan that was overtly different from her sheltered home enclave. Her connection to her artistic path did not click in these surroundings. Instead, she pursued an education at the City College of New York, where she focused on history, political science, and literature. The knowledge she acquired, combined with her intrinsic sensitivity to social inequities, would provide the backbone of her political awareness. America was in the throes of facing hard truths about its own racial inequalities. All these factors were integral to forming Graupe-Pillard’s perspective.

An interest in Marxism and Russian culture led her to the CUNY Graduate School and an assistantship in “Russian Area Studies.” Not unlike many young women of that time, Graupe-Pillard married at the age of 21, “in order to get out of the house.” Yet what she thought was her personal and educational course ended up being subject to the same social upheaval that others were experiencing. The catalyst for her epiphany came when she covered a wall in her apartment with a huge mural executed in magic marker. A friend encouraged her to consider attending art school.

As a result, 1964 turned out to be a pivotal year for Graupe-Pillard. She shed her marriage and graduate school, and signed up at the Art Students League. There, she studied for several years concentrating on classes in life figure drawing. She received the George Bridgman Memorial Scholarship, awarded to her by juror Philip Guston. Beyond the financial ramifications, it served to validate her choice to pursue art. Marshall Glasier, who had studied with George Grosz, was one of her mentors. When pressed about her painting instructors, Graupe-Pillard said with a touch of irony, “I am really a self-taught painter. My teachers were Cezanne, Soutine, Van Gogh, and Goya.”

Deciding that she definitively didn’t want children, and there would be “no hausfrau for this frau,” Graupe-Pillard set her sights on a different kind of lifestyle. She wanted to “live in a loft” and focus on her art. She decided to uproot herself and start a new chapter of her life in New Mexico. She called it, “Being part of the hippie movement that embraced expanding human potential.”

In Albuquerque, Graupe-Pillard found a studio and wrangled free rent by taking over the role of the superintendent. She joined other building residents who were engaged, nationally exhibited artists. They formed a close-knit group that argued and exchanged ideas. Numerous friendships were built with those who were affiliated with the University of New Mexico, as well as Tamarind Institute. It was during this period that Graupe-Pillard met the man who became her second husband, a student of cultural anthropology.

Talking about the body of work that she produced from 1968-1974, Graupe-Pillard related, “It was all about place and light. The setting was so vast.” She acknowledged the influences of Mark Rothko and Helen Frankenthaler, and discussed her method of directly pouring paint on unprimed canvas—“never to be touched by human hands.” Using the format of “the series” (a mainstay of her work), Graupe-Pillard assembled a grouping of paintings under the title New Mexico Band Paintings. Although at first these canvases appear to be totally disconnected to ensuing works, there is a clear link to the intensity of how Graupe-Pillard still uses her colors.

The inclusion of several pieces at the Santa Fe Museum encouraged Graupe-Pillard to approach galleries and collectors in the vicinity. She also began to think about “coming home.”

Graupe-Pillard moved to Long Branch, New Jersey in 1974. She connected with the Razor Gallery in Soho, where she exhibited the Band Paintings. Her physical surroundings, including the oceanfront, served as new inspiration. Graupe-Pillard started to draw again, reconnecting with figuration. Most importantly, she learned photography, which would become a constant tool as well as a basis and filter for seeing.

“The 70s,” Graupe-Pillard reminisced, “were a heady time. I was informed by feminism. The movement was very important because it gave us chances we didn’t have before.” She pointed out how presently, she views feminism as akin to ageism.

From 1977 through 1981, Graupe-Pillard worked on painting “realistic” male and female nudes.

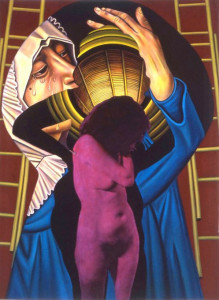

Woman With Blue Robe

1980

Oil/Canvas

72” x 48”

This began a period of seeking models that were out of the mainstream—and often on the peripheries of society. The nudes led to clothed people, and an examination of their inner psychological profile as intuited through their external presentation. A 1981 exhibit at the Drawing Center showcased charcoal drawings of People and Hats, followed two years later by an exhibit at the Bernice Steinbaum Gallery.

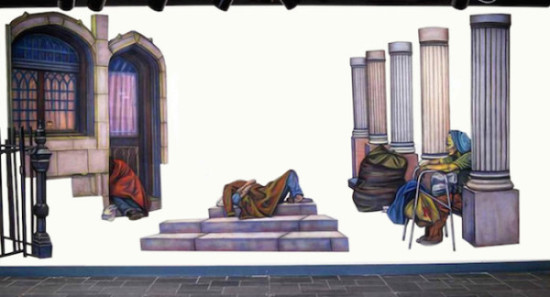

Graupe-Pillard talked at length about the “irony” of her use of pastel, often categorized as a “woman’s tool.” In addition to “using a traditional medium in an untraditional way,” she liked the rapidity of the process. For a decade (1984-1994), Graupe-Pillard used pastels on canvas, pushing the envelope by then cutting them out and creating wall groupings as installations. She said, “I saw it as the perfect medium to document the often difficult art of survival in New York City. The directness of the material mimics the speed and excitement of the urban environment—and that includes the contradictory elements of squalor and glamour.” Once again, Graupe-Pillard drilled down on making those denizens who are too often “invisible, permanently visible.” In 1993, at Kean University, Eugenie Tsai curated a ten-year retrospective of Graupe-Pillard’s pastels. Included was an Architectural Installation, which encompassed the verisimilitude of life on the street.

Architectural Installation

1993

Pastels/Cutout Canvas

140” x 360”

One of Graupe-Pillard’s strongest series was Boy With a Gun (1987-1993). A one-person show at Klarfeld Perry Gallery in 1993 garnered a series of reviews in the art media. Using a silhouette of a boy with a gun (“I use the silhouettes as containers.”), Graupe-Pillard commented on a continuum of narratives from gang violence to state sponsored violence—capital punishment. Several of the pieces will be part of a November 2014 exhibit, Evil: A Matter of Choice, at the HUC-JIR Museum in Manhattan.

Boy With A Gun/Execution

1992

Pastels/Cutout Canvas

89” x 49”

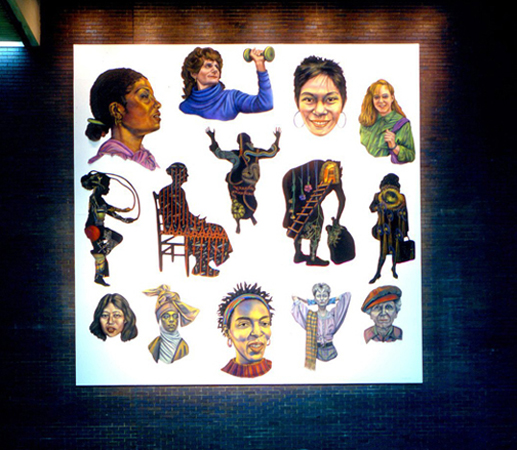

In conjunction with the 1992 Democratic National Convention, tagged the “Year of the Woman,” Graupe-Pillard was commissioned to deliver a massive installation at the Port Authority Bus Terminal in Manhattan. A full range of her figures and motifs were on view.

Wonder Women Wall

1992

Pastels/Cutout Canvas

20’ x 20’

Consistently tapped for public art projects (which along with teaching helped support Graupe-Pillard financially), her commissions for Shearson Lehman American Express, AT&T and New Jersey Transit led to an exploration and construction of freestanding sculptures. Her accomplishments in that field earned her an invitation to teach at the National Academy Museum, where she directed the Edwin Austin Abbey Mural Fellowship Workshop for eight years.

People Railings — Garfield Station

1999/2000

Porcelain Enamel/Steel/Wood

72” x 108” x 3”

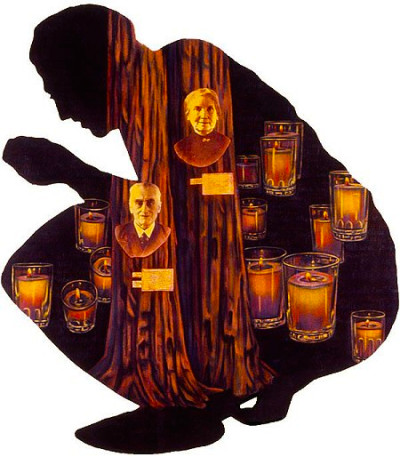

The period of 1990-1993 marked the period when Graupe-Pillard devoted herself to perhaps one of her best known and widely exhibited series. Nowhere to Go: One Family’s Experience dug into Graupe-Pillard’s examination of the Holocaust. It was mounted at both the New Jersey State Museum in Trenton and at Rider University. Comprised of ten identical pastel on canvas cut-outs, it employed the shape of a crouching figure intently examining something in its hand. The outlined individual served to encompass a range of symbolic scenes. Family letters, photographs, and oral histories culled from her parents served as the emotional armature. The names of over seventy relatives who perished in the death camps were integrated via text. In Family Tree, Graupe-Pillard engages the viewer with photographs collaged onto a backdrop of Yahrzeit candles, the traditional way Jews observe the anniversary of a death. In these circumstances, the exact dates are unknown. The totality goes beyond the specific to speak to the horrors of “modern genocide,” from Cambodia to Rwanda.

Nowhere To Go II — Family Tree

1990

Photographs, Alkyd, Pastels/Cutout Canvas

79.50” x 70″

The Keyhole series can be viewed as the beginning of a “formal” incorporation of photography into the work, with the computer as an essential part of the practice. Through its use, Graupe-Pillard engages in major mash-ups with elements she finds from “scavenging through art books.” All are assessed through the lens of the camera—and then combined with Graupe-Pillard’s own creative history.

Keyhole Series — Grace/Weeping Virgin

1995

Photograph/Alkyd/Oil/Canvas

84” x 60”

In 2001, Graupe-Pillard was impacted by two major events. The near-death of her husband, and the attack on the World Trade Center. Once again, she turned to her art to process the experiences. The result was the Manipulation/Disintegration/Displaced series. Forms became splintered, as they broke apart. Shapes were configured and reconfigured. Up close, they read as abstract jigsaw puzzles of colors and contours. Upon stepping back, they become narratives about the shattered lives of refugees in Darfur, Afghanistan, Iraq, and Gaza.

Women Running

2006

Oil/Alkyd/Canvas

54” x 84”

When I visited Graupe-Pillard at her studio, Fallout: The Confetti of War was on the floor waiting to be stretched. Recently completed, the source photo captured a car bombing incident in the Middle East. It will be shown in 2015 at the Carl Hammer Gallery in Chicago, as part of a solo show.

Fallout: The Confetti of War

2014

Oil/Alkyd/Canvas

66” x 90”

Using contemporary technology to expand her vocabulary, Graupe-Pillard developed Interventions—It Can’t Happen Here. She conjured scenarios that were particularly powerful, and that now feel prescient in light of the street scenes in Ferguson, Missouri.

23rd Street Prisoners

2005

Archival Pigment Print

22” x 30”

The digital prints, which are processed either in color or black and white, speak to fear, xenophobia, the role of the media in war, and truth versus reality. The trauma of 9/11 unleashed a full range of reactions from the American people—from the desire for revenge to a call for reflection. Graupe-Pillard takes on the specter of Gitmo and Abu Ghraib, the issue of detention and torture, and places them in our own backyard. Given Graupe-Pillard’s familial link to Nazi history and the question of individual culpability, perhaps there is an unconscious link. Graupe-Pillard challenges the viewer. She is artist as provocateur asking, “As an ordinary citizen, do you think this is right? What action will you take?”

During my visit, our conversation turned from her work to a look back on the trajectory of her career and art world trends. Graupe-Pillard recounted, “I was exhibiting regularly, every two years, in New York City and Europe. I was in fairs and had collectors from private and corporate collections. Then in 1987, the market crashed. By that time, I began doing public art projects. I continued to show in the East Village at Hal Bromm Gallery. Later, in Soho at Donahue/Sosinski, and in Chelsea at The Proposition.” Reflecting upon the difficult road of being an artist, Graupe-Pillard maintained, “A career in art is like a wave. It’s up and down. I was lucky, and one thing led to another. You need people who really respond to the work; someone who trusts their own judgment and has the power to give you a show. You’ve got to stick with it, for as long as you can do it.”

Continuing with a discourse about ageism in the gallery scene, Graupe-Pillard noted, “I no longer want to go to a lot of openings and schmooze. I don’t actively solicit galleries, even though I think I’m in the most fertile period of my work.” She sighs and adds, “Think of Titian and Goya in their nineties. Monet is a good example. When people ignore older artists, I think it’s limiting. Many older artists keep growing.”

Graupe-Pillard regularly engages a wide audience with her latest output— via Facebook—specifically sharing her self-insertions into art works from ancient Greece to Rodin and Benglis. The comments about her latest exploits are gleeful.

Graupe-Pillard related, “I’m always thinking about a lot of things. I’m constantly working. As an artist, I don’t consider the saleability of the paintings. The work is a commentary on the age I have lived in. I am a documentarian, recording the critical moments of my life and those of society.”

As Graupe-Pillard repeated throughout our conversation, “In the end, the work has a life of its own.”

Photos courtesy of Grace Graupe-Pillard

This article is from the series “Evolution of an Artist”

Great article! Congratulations to the artist and the writer.

Graces’ work is both full of ideas and visually exciting. It needs to be seeing to be appreciated, not like much art today that is all words. Her art has what makes good art: Great concepts and emotions within the history of art.

Freddy – thank you – really appreciate your comment.

A remarkable portrait of a remarkable artist, exhibiting an embarrassment of riches, with courage and humanity topping the list.

Robert – lovely words – many thanks.