Egon Schiele: Portraits at Neue Galerie

In 1963, Dr. Alessandra Comini saw a small exhibit of Austrian Expressionists. It was her first time viewing the work of Egon Schiele. She described it as “an apocalypse that changed my life.” It put Comini on a path to becoming one of the foremost scholars on Schiele and his oeuvre. Now, at the Neue Galerie through January 2015, Comini has organized an exhibition of Schiele portraits. Roughly 125 drawings, paintings, and sculptures comprise the show.

I had the opportunity to interview Comini on-site at the Neue Galerie, and learned the back story of her journey. Comini related the impact of first seeing the artist’s work. She said of Schiele, “I never saw anybody so frank. He had a searing drawing style. In his content, there was a baring of his soul.”

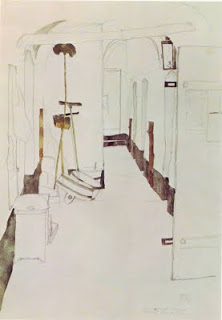

Comini reached out to Schiele’s sisters by mail, and they responded to her inquires within two weeks. Traveling to Austria, empowered by her fluency in German, she visited the village of Neulengbach where Schiele had been imprisoned in April 1912. Imprinted in her mind, Comini had a visual image of the drawings Schiele had made of his cell during his days of incarceration. Comini sought out the small room with the carved initials of MH, which had belonged to a previous prisoner. She recognized the hallway from drawings of a standing mop and bucket.

I Feel Not Punished but Cleansed! 1912

I Feel Not Punished but Cleansed! 1912

Gouache, watercolor and pencil

Graphische Sammlung Albertina, inv. 31025. (Graphische Sammlung Albertina)

Although there were efforts to deter Comini from entering the District Courthouse, which housed the former prison, she slipped in after being turned away. Following a set of stairs down into the cellar, she located Cell #2, where Schiele had been. Everything was identical to Schiele’s imagery, except for a wooden beam that had begun to sag. Comini was the first person to locate and visit Schiele’s jail cell, and she documented the moment with “an old rolleiflex camera.”

Comini views Schiele’s imprisonment as a turning point in both his art and his development as a person. He had been arrested on charges of kidnapping and raping a minor. Schiele was cleared of those allegations, but found guilt of “immorality for public display of indecent imagery.”

During those days of imprisonment, Schiele did his first self-portraits without a mirror. Comini stated that he went from “agony to empathy—maturing.”

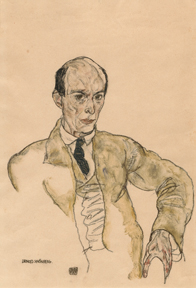

Central to Comini’s conception of the exhibition is a room devoted to recreating Schiele’s prison experience. Presented is documentation of the physical space where Schiele was locked up, works on paper, and a small sculpture of a head he made out of bread. Comini specifically chose a composition by Arnold Schöenberg to be the auditory component of the room’s experience. Schöenberg was part of Schiele’s circle of creatives and intellectuals in Vienna, and would be a subject of a portrait in 1917.

Portrait of the Composer Arnold Schönberg, 1917

Portrait of the Composer Arnold Schönberg, 1917

Watercolor, gouache, and black crayon

Photo: Courtesy of Neue Galerie

Rather than present the works chronologically, Comini chose to hang the show delineating them by categories. The six groups are: Family and Academy; Fellow Artists; Sitters and Patrons; Lovers; Eros; Self-Portraits and Allegorical Self-Portraits.

Upon entering the exhibit, there is a large photo of Schiele. To the right, a long hallway with Schiele’s personal and artistic timeline leads directly to an open view of his painting, Portrait of the Artist’s Wife, Standing.

Schiele was born in 1890, in a suburb of Vienna. At the age of sixteen, he was accepted at the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna, where he was the youngest student enrolled. In 1907, he began a lifetime friendship with Gustav Klimt, who would mentor and influence him. The following year Schiele was included in his first group show, where his images were seen by the collector Heinrich Benesch, who became a patron and friend.

Klimt invited Schiele to exhibit four paintings at the 1909 “Internationale Kunstschau.” A dissatisfaction with the old guard led Schiele and other artists to form what they termed Neukunstaruppe—the “New Art Group.” At this time, Schiele met the art critic Arthur Roessler, who evolved into a friend, subject, patron, and biographer. Roessler would publish an article on Schiele’s first solo exhibit in Vienna.

By the age of twenty, Schiele had found his voice and personal style. He largely concentrated on self-portraits, which he posed for in front of his mother’s full-length mirror.

The first ten works in the “Family and Academy” room testify to Schiele’s ability as a classical draftsman. Comini suggested that three of the works in this grouping “encapsulated” Schiele’s career. Portrait of Gerti Schiele is clearly indebted to the impact of Klimt, specifically in the richly patterned areas of the subject’s dress.

Portrait of Gerti Schiele, 1909

Portrait of Gerti Schiele, 1909

Oil, silver, gold-bronze paint, and pencil on canvas

Photo: Courtesy of Neue Galerie

His 1916 watercolor, gouache, and pencil on paper portrait of his father-in-law, Johann Harms, bear the signature markings and iconography that would become identified with Schiele. Specifically, the focus on the hands, knuckles accentuated with sienna and touches of blue—motifs that are repeated in the face.

It is in the oil painting of Harms that a post-prison darkened palette is reflected, with what Comini called “a milder environment.”

Portrait of Johann Harms, 1916

Portrait of Johann Harms, 1916

Oil with wax on canvas

Photo: Courtesy of Neue Galerie

The oil, gouache, and charcoal on canvas from 1910, Portrait of the Painter Karl Zakovšek, fits Comini’s description of Schiele’s quintessential placement of his subject in “an existential state.” She related, “There is no environment. There is no chair or room. Schiele has stripped away all surrounding. The figure is centralized on a diagonal lean.” As Comini explained, “With Schiele, there is a constant search for identity and authenticity.” She added, “Hostile critics called it ‘pathological portraiture.’” Rather, as Comini pointed out, it was a contrast between “façade and psyche; rational versus irrational; schein to sein (appearance to being).”

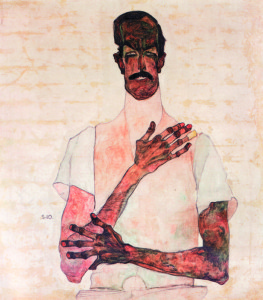

In “Sitters and Patrons,” the portrait of Dr. Erwin von Graff stands out due to qualities that render the physician in an eerie and almost sinister way. Von Graff was a gynecologist who provided Schiele with the favor of an abortion for one of the artist’s companions.The face, hands, and left arm of the doctor are mottled and dark brown in places, giving them the quality of burnt flesh. The right arm is stretched across the chest in what Comini calls “a language of gestures.” The bony fingers with prominent knuckles get an additional point of reference, with the accent of a small bandage on the ring finger of the right hand.

Portrait of Dr. Erwin von Graff, 1910

Portrait of Dr. Erwin von Graff, 1910

Oil, gouache, and charcoal on canvas

Photo: Courtesy of Neue Galerie

As Schiele picked up more commissions, he had to please his patron’s whims and desires. An example is Portrait of Carl Reininghaus (1910), where the sitter is portrayed wearing his lederhosen. Additionally, Comini noted that Schiele “obliged certain collectors with his erotic pictures—which found no lack of clients.” It was an opportunity for Schiele to mine additional income.

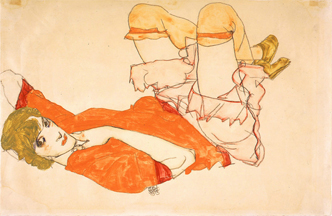

In “Lovers” we see studies of Wally, Schiele’s longtime companion, and his wife Edith. Wally in Red Blouse with Raised Knees captures the essence of what comes to mind for many when they think of Schiele. That of a woman in a pose where legs are accented by colored stockings accompanied by an air of openness and availability.

Wally in Red Blouse with Raised Knees, 1913

Wally in Red Blouse with Raised Knees, 1913

Watercolor, gouache, and pencil

Photo: Courtesy of Neue Galerie

Although in 1917, Edith would be painted with garters and stockings in, Portrait of the Artist’s Wife Seated, Holding Her Right Leg, the flesh of her left thigh exposed, his 1915 full-length portrait revealed a very different story. Comini conveyed that Edith “hated the portrait” as it showed her as “fragile and unsophisticated.” Although the material and folds of the dress are meticulously rendered, the facial expression is blank. Edith’s hands resemble rigid claws. Part of Schiele’s motivation in marrying Edith was the hope that it would delay his army service. Although he saw Edith as a “petite bourgeoisie coquette,” she was of a suitable background for marriage—unlike Wally. Schiele harbored hopes of maintaining relationships with both women, post-nuptials, a concept that was tersely nixed by Wally and Edith.

Portrait of the Artist’s Wife, Standing (Edith Schiele in Striped Dress), 1915

Portrait of the Artist’s Wife, Standing (Edith Schiele in Striped Dress), 1915

Oil on canvas

Photo: Courtesy of Neue Galerie

In the “Eros” section, there are nude girls and women partially clothed, sometimes with lifted skirts or just wearing stockings. Genitals are pronounced. Observed in a Dream (1911) presents a woman, face partially covered, lying on her back while spreading open the labia of her vagina. The Red Host (1911) situates Schiele with a paramour, seated beneath him. A huge, erect phallus extends up from her hand to his mid-chest area, blending in with the alizarin crimson of his shirt. Reclining Woman with Green Stockings (1917) uses black crayon and gouache to ground his figure, giving it a more concrete feeling than his watercolor and pencils works.

Comini construes Schiele’s “obsessive preoccupation” with sex as directly correlated to his father’s deterioration and death from syphilis. The disease, which can be contracted through birth, affected two of his siblings, who died as well. Comini interprets Schiele’s immersion in sexuality as a form of warding of the “specter of syphilis,” akin to a form of “white magic.”

In the “Self-Portraits and Allegorical Self-Portraits,” after the early academic portraits of 1906-1907, the works evolve to the edgy, angular imagery characteristic of Schiele’s approach and technique. Tufts of armpit or pubic hair take on the appearance of electrified wire. Free-floating heads are haloed by white gouache. Hands are highlighted and elongated. A utilization of the brown hues that were apparent in the von Graff portrait is seen. One painted head shows Schiele with a shirt, bow tie, and jacket that melts into a simple line drawing. Triple Self–Portrait combines three facial expressions, while another 1914 piece renders Schiele as the martyred St. Sebastian.

In April of 1918, Edith became pregnant. That same year, Schiele completed The Family (Squatting Couple). Edith would die six months later from the influenza epidemic. Schiele would fall ill as well. He died on the day of Edith’s burial. He was 28 years old.

The Family (Squatting Couple), 1918

The Family (Squatting Couple), 1918

Oil on canvas

Photo: Courtesy of Neue Galerie

In The Family, Schiele continued to include visual language from his previous work in his own self-portrayal. He looks directly out at the viewer. His shoulders are tilted, his left arm is exaggerated in length, and his right arm crosses his chest. The result is contorted. Yet, Edith’s body is portrayed more realistically. Her expression is one of sadness, as she looks off into space. The child, who was never born, has a doll-like quality. The face is predominately white, as opposed to the flesh tone of the ear, giving the appearance of a mask.

Schiele’s work had an unmatched intensity. It’s impossible to gauge what path he would have taken if he had lived, or how he would have navigated Nazi rule. By the time of the Anschluss, Schiele would have been middle-aged. Comini noted that even in his youth, Schiele was was “apolitical, unlike Oskar Kokoschka.” The responsibility of fatherhood was about to impact him, and he had ambitious plans to convince Viennese luminaries to join together to create a new unity of the arts.

Just as Sigmund Freud upended and challenged the way society viewed the psyche and sexuality in fin-de-siècle Vienna—Schiele reached the same results with emotionally charged works that reflected his inner turmoil, desires, and fantasies. One hundred years later, they continue to resonate just as vividly in the 21st century.