Marisol: Sculptures and Works on Paper at El Museo del Barrio

Integrated into the exhibit Marisol: Sculptures and Works on Paper at El Museo del Barrio, are numerous wall-text quotes. Resonating deeply are the artist’s words from 1989:

“I’ve always wanted to be free in my life and art. It’s as important to me as truth.”

While others in the art world were intent on categorizing Marisol’s work within one particular school or another, Marisol continued to explore the subjects and mediums that spoke to the immediacy of her creative impulses.

Born in Paris in 1930 to Venezuelan parents, Maria Sol Escobar has lived in Caracas, Los Angeles, Paris, Italy, and New York City—where she currently resides. Leo Castelli showcased Marisol’s talents in 1957 when he put her in a group show. Six months later, she secured a solo show at his gallery.

Ignoring the vagaries of the art scene, Marisol explored her own vision and imagery undeterred by the knowledge that her direction was not always in tune with the prevailing sensibilities. At times, an ongoing background chatter threatened to overshadow her accomplishments. These included her friendship with Andy Warhol, her physical beauty, and the critics who originally lauded her but became detractors later in her career.

Marisol racked up abundant early accolades. She was included in the 1961 Museum of Modern Art exhibit, The Art of Assemblage, and represented Venezuela in the 1968 Venice Biennale. She found a nurturing home at the Sidney Janis Gallery from 1964-1993. During the decade of the 1960s, she made almost one hundred sculptures.

The Memphis Brooks Museum of Art originated this exhibition of Marisol’s work in June 2014. At El Museo del Barrio, it stands as the first solo show for the artist in a New York museum. I was able to speak with Executive Director, Jorge Daniel Veneciano, and curator Rocio Arando-Alvarado, at the time of my visit.

Veneciano, who took over the museum’s helm nine months ago, shared his future goals. On the agenda is a five-year plan committed to showcasing women artists—with scholarship as a key element of the presentation. Securing the Marisol exhibit was integral to setting the tone for his strategy. As Veneciano escorted me on a walk-through, he spoke animatedly about the “conceptual installation” and how the differently colored walls established specific relationships with the work. He named a dark salmon backdrop panel as “Marisol pink.” “Every room has a portal pulling you in,” he said. “We want to do things differently. We want to bring new ideas to exhibition practice.”

Reflecting on Marisol’s career, Veneciano said, “This is an important woman artist who merits the attention. She was a woman in a man’s genre—which was Pop art. She was working with cultural iconic images, but they didn’t look like Warhol or the male version of Pop art.” Veneciano stated, “As a result, Marisol was displaced and dismissed.”

The show is not structured chronologically. Rather, Veneciano wants to highlight an examination of Marisol’s oeuvre with a nod to her “broader experimentation.” Pointing to a drawing from 1974, he remarks upon the “tension in her work” and the integration of “color with dark subject matter.” Veneciano emphasized the “ironies” that Marisol pinpointed, while “mixing metaphors and reversing perceptions.”

Standing with Arando-Alvarado in front of the double lithograph Diptych, she noted, “Women artists of this generation didn’t necessarily think of themselves as feminist, but this work is a really powerful feminist statement because it underscores her presence.”

Upon entering the exhibition, the visitor is introduced to Marisol’s universe via a large black and white photograph of the artist in her studio, where she is surrounded by wood cutting tools. The infant Jesus, from The Family, is on the table in front of her. In the background, an out of focus Mary can be seen behind her.

The Hungarians, from the 1950s, introduces a theme that will be reiterated and reexamined throughout the years. A family unit is assembled and placed on a surface—wood planks with four carriage wheels attached. There are touches of color on the mother’s lips. The whites of all the eyes have been subtly demarcated.

The Hungarians, 1955

The Hungarians, 1955

Polychromed Wood

36.50” x 27” x 20.50”

Completed two years later, Queen melds a carved bust out of wood with a terracotta crown-like structure. The markings in the hair recall Picasso’s riff on Velázquez’s Las Meninas. The format of the terracotta portion, with separate and interlocking components, points to the bronze pieces Marisol would cast in 1959. It also recalls the Mexican “Tree of Life” ceramic candelabras.

Queen, 1957

Queen, 1957

Wood and Terracotta

28.75” x 13.50” x 9”

Marisol delves into the psychological impact of the family on the individual. In Family Portrait, a photograph from the early 1930s serves as a departure point for her print. An initially straightforward representation, with a medallion-shaped depiction of her parents placed above a rectangular family grouping, morphs into greater complexities. Hands, fingers, profiles, and unidentified protuberances then envelope that imagery. They are the beginnings of a visual vocabulary that will be employed by Marisol recurrently.

Family Portrait, 1961

Family Portrait, 1961

Lithograph

29.06” x 23.125”

In Mi Mama y Yo, Marisol combines color and materials to probe her relationship with her mother. There are repeated rhythms throughout. The fluidity of positive and negative space travels up from her mother’s red shoes, to the back of the bench, ultimately reaching the latticework of the umbrella. The latter is painted a sunny yellow on the portion facing outwards, but a darker blue on the inside. Mother and daughter share two different tonalities of pink. Most striking is that the small daughter is holding the umbrella—tasked with the responsibility of protecting both her mother and herself. The child’s face is solemn. Knowing that Marisol’s mother committed suicide when she was eleven adds another layer to perceived interpretations.

Mi Mama y Yo, 1968

Mi Mama y Yo, 1968

Steel and aluminum

73” × 56” × 56”

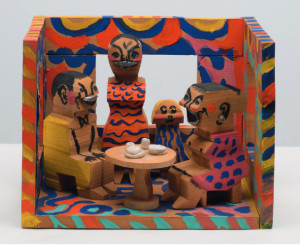

Was Marisol’s return to the use of the family dynamic her way of trying to restructure and control the narrative of her personal history? In Doll House, made twenty years later, the depiction of three adults and one child gathered around a table to “break bread” is anything but a comforting environment. The bottle top mouths, with their sharp and jutting edges, are unambiguously predatory. The smallest figure, the only one with a painted mouth, has a facial expression that combines both fear and confusion. This is a dollhouse to escape from.

Doll House, 1987

Doll House, 1987

Polychromed Wood and Metal

10.75” x 13.75” x 10”

Focusing on herself in Diptych, Marisol offers a two-part print that reads as one piece. The top is printed in gray; the bottom in black. Produced at the workshop of Tatyana Grosman (ULAE), Marisol inked her body and then pressed herself to the lithographic stones. She then went back in and reworked areas, adding a fractured heart and the protuberances that read as fingers or projectiles. One extends from her left ankle, possibly responding to the hole in her right foot. The footsteps appear to be leaving the self-portrait behind. The droplets in between the feet connect to a similar shape emanating from near the artist’s left hand. It’s a self-portrait that is both nuanced and powerful in its declaration of agency.

Diptych, 1971

Diptych, 1971

Lithograph

21.50” x 17.187

At the end of the 1960s, Marisol was commissioned by the Brooks Memorial Art Gallery (which evolved into the Memphis Brooks Museum of Art) to create a Nativity scene. The opportunity allowed her to portray the most famous family in art and world history.

The Family, 1969

The Family, 1969

Wood, Plastic, Neon, Paint

88” x 56” x 65”

Her Madonna is striking, a palpably powerful presence. The neon halo surrounding her head is intricate and multilayered—a stark contrast to Joseph’s single band of light. With a richly bejeweled and painted torso, she is the star of this show. Her womb opens up to reveal a mirrored box. Mary’s countenance takes its features from a plaster cast of Marisol’s own face. The hands (duplicate left appendages) are not praying, like Joseph. Rather, they form a pose of benediction, reflecting empowerment and calm control. All three figures are brown complected. The baby Jesus is carved in a static, yet proactive position. Marisol chiseled him with precision, from the creases in the bottom of his feet to his explicitly presented penis and testicles. The scene is contained within a perimeter of AstroTurf.

Between 1977 and 1981, Marisol produced the series, “Artists and Artistes.” Included are a humorous Magritte, and a seated Picasso—who has a knot of nails coming out of the spot where his heart would be. One cannot ignore the allusion to the women in his life. Marisol has endowed him with two sets of plaster cast hands, perhaps a symbol of his expansive creativity. The tool markings leading to his feet suggest the hirsuteness of the minotaurs found in his paintings and prints.

Picasso, 1977

Picasso, 1977

Wood and Plaster

53” x 29” x 29”

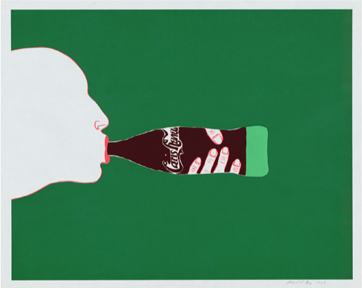

Paris Review speaks to Marisol’s connection to the Pop art movement. A flat area of green serves as the backdrop for a woman’s profile. A Coca-Cola shaped bottle, bearing the logo “Paris Review,” is inserted into her parted lips. It harkens directly back to her 1962 sculpture, Love.

Paris Review, 1967

Paris Review, 1967

Silkscreen

32.50” x 26”

Beyond commenting on society and mass culture, Marisol dug beneath the surface to engage with ideas that were political. She had a strong awareness about the civil rights disparities between blacks and whites in the United States. She also knew that Venezuela was not without its own legacy of slavery. In 1961-62, Marisol worked on The Blacks, a sculpture that scrutinized structural racism and sexism. The Vietnam War and the turmoil of the 60s were all an acute part of her consciousness.

In the early 1990s, Marisol embarked on a succession of drawings and sculptures with Native Americans as the subject. She culled her images from the work of photographers. Her pastel drawing of Black Fox (1992) evolved from a photo by Charles Milton Bell. The sculpture, Horace Poolaw, is based on Kiowa photographer Horace Poolaw’s image of his young nephew.

Horace Poolaw, 1993

Horace Poolaw, 1993

Wood and Mixed Media

76” × 40.50 × 32”

Marisol crayons on the wood to demarcate feathers in the headdress. The two fists are placed facing opposite directions. While one is turned inward, the other faces out in what can be construed as a symbolic gesture of defiance and resistance. Placed on a base with wheels, there is an additional caustic note. The planks are scavenged from discarded police barriers and bear the message, “Police Line. Do Not Cross.” Entwined are the subtexts of forced migration, state authority, and the right to one’s own culture.

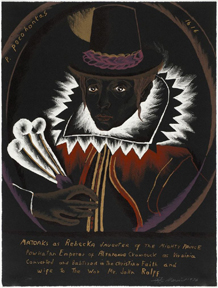

Situated in close proximity to Horace Poolaw is a handsome, but disturbing, print of Pocahontas. It is fashioned after an engraving by Simon Van De Passe, which depicted a Christianized Pocahontas in European dress, married to the Englishman John Rolfe. The colors and angles have a jarring effect. The viewer is left to contemplate Pocahontas shedding her personal history to adopt an Anglo existence.

Pocahontas, 1975

Pocahontas, 1975

Lithograph

26.125” × 19.75”

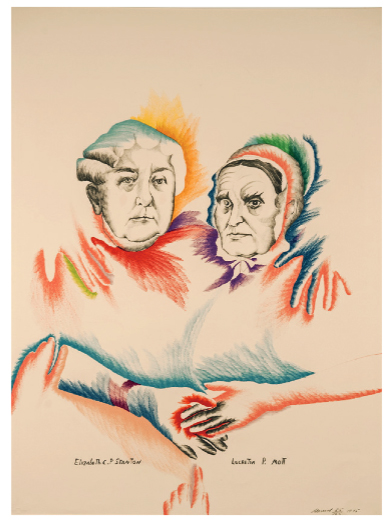

In the final gallery, there are three works that speak to Marisol’s connection to social inequities. In Bishop Desmond Tutu, Marisol conveys both the strength and the resilience of the South African religious leader and activist. She pays homage to Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott in Women’s Equality. With a hand reaching up from the lower edge of the page, index finger pointing toward the two women, Marisol connects herself to their lineage.

Women’s Equality, 1975

Women’s Equality, 1975

Lithograph

42” x 30”

Strategically placed against a red wall is Boy With Empty Bowl, exhibited at The International Art Show for the End of World Hunger. In the accompanying catalogue a quote from Marisol said in part, “…I would like to see a more balanced way of sharing food and life.”

Boy with Empty Bowl, 1987

Boy with Empty Bowl, 1987

Wood and Utensils

24” x 17” x 16”

The Funeral encapsulates America’s national tragedy, the assassination of President Kennedy. Using the quintessential moment when “John-John” saluted his father in a final farewell, Marisol delivers a full-sized John Jr. with a diminutive funeral procession at his feet. The caisson, with the coffin draped in the country’s flag, is placed directly in front of John’s figure.

The Funeral, 1996

The Funeral, 1996

Oil and crayon on wood

56” × 122.25” × 11”

Directly adjacent to The Funeral, is I Did my Future. At the bottom of the drawing is a baby. Whether intentional or not, I found the correlation between the two children hard to ignore. The drawing depicts violence and shocking aggression. Numerous guns are being shot point-blank at a central figure. One penetrates the mouth and comes out the back of the head. There is a grouping of hands. The brutality can be read as representing a number of different destructive behaviors or as a statement on America as a violent culture. The baby who is just learning to lift its head looks out at the viewer as if to ask, “What kind of world have I been born into?”

I Did My Future, 1974

I Did My Future, 1974

72” x 83.10

Pencil, Colored Pencil, and Crayon on Paper

On my way out, I stopped to speak with Alicia Grullon, who was setting up her work in an area near the show’s entrance. She was there as part of a six-week residency showcasing contemporary artists. Grullon told me that she had been “very influenced by Marisol,” and was “acutely aware of all the politics of the art.” We discussed the intensity of the work and the challenges Marisol had faced. Grullon stated with admiration, “Her persistence to voice is inspiring.”

Photos: Courtesy of El Museo del Barrio

On View through January 10, 2015

El Museo del Barrio

1230 Fifth Avenue

New York City

This is a great article about a great artist that have been neglected for a long time. There’s so much to see, learn and appreciate from Marisol’s work.