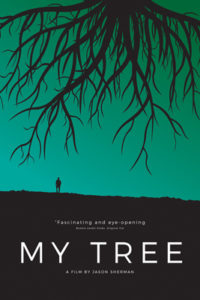

Canadian Jason Sherman Examines the Legacy of the Jewish National Fund in Documentary “My Tree”

“My Tree,” a documentary directed by Canadian playwright and filmmaker Jason Sherman, follows his quest to learn the backstory of a tree planted in Israel on the occasion of his Bar Mitzvah in the 1970s. The Jewish National Fund (JNF) connected with Toronto shuls, thus allowing 13-year-old boys to have a tree dedicated in their names.

Sherman relates a version of greening Israel that impacted the Canadian diaspora, the fourth-largest Jewish community in the world. He delivers his opening comments with sarcasm and self-mockery while he schleps around Israel looking for his almost fifty-year-old tree. It was supposed to be his “stand-in” and connection to Eretz Yisroel.

Mordant humor informs the history of the JNF and its marketing strategies. A cartoon of collection boxes dancing the hora while holding bags of money. The poster with a strong, tanned Sabra and his shovel. Video clips reveal celebrities from Kirk Douglas to Albert Einstein as they dig into the earth.

The Holocaust gave an “urgency” to the situation. Keren Kayemet L’Yisrael. A perpetual fund for Israel. The goal was to make the desert bloom. Instituting a personal attachment was the impetus. The tagline was, “This is your forest.” And it worked, resulting in 240 million trees.

The JNF chose pine trees, possibly because they reflected the abandoned landscapes of European countries. More probably, it was that they grew rapidly. Yet, with small roots and high flammability, they were problematic. A major fire on Mt. Carmel in 2010 exemplified these problems. Only the indigenous oak trees survived.

Sherman hires a “tree searcher” to begin the quest. She digs into the copious records of the JNF, housed in the Jerusalem Central Zionist Archives. Canadian tree donations are primarily grouped in “Canada Park.” The problem is presented. Jews didn’t own land in that area.

A visit to the Eshtaol Nursery sets the scene for a meet-up between Sherman and a JNF representative who tells him he needs advance permission to shoot any footage. Sherman notes, “The JNF didn’t want to talk to me. Not about my tree; not about any tree.”

Undaunted, Sherman connects with Alon Rothschild, the Biodiversity Policy Manager at the Society for the Protection of Nature in Israel. Pointing to a tract of land, Rothschild asks, “Should we have trees here? Why? These are the last grassland hills in the area. Why do you need another pine forest?”

Things get heated when a JNF employee comes along and enters the conversation. Sherman laments, “Maybe this could be my tree.” The representative plays straight man to Sherman stating flatly, “I would not like to comment on it right now.” (Another scheduled conversation was halted on the spot when the JNF spokesperson determined that Sherman was there to “politicize trees.”) It feels like dialogue from the theatre of the absurd.

By the time Sherman visits his cousin, who has made Aliyah to Israel, the tenuousness of the situation rises to the surface. She talks about how the country has gone downhill, using the word apartheid.

This is a foreshadowing of Sherman’s conversation with Eitan Bronstein Aparicio, founder of Zochrot and co-founder of the De-Colonizer. Aparicio wants to deconstruct Israeli mythology and bring attention to the Nakba, the Palestinian word for their “catastrophe” of 1948.

Aparicio tells Sherman about three decimated Arab villages: Beit Nuba, Yalu, and Imwas. “These villages were totally destroyed. People were expelled. It was bulldozed and dynamited.” He adds, “An occupying army is not allowed to expel a population, destroy homes, or prevent people from return. All this are war crimes. Definitely, yes.”

At one site, the signs in Hebrew label the area as Roman ruins. Aparicio shakes his head. “That’s not a Roman bathhouse,” he says, pointing to the structure. “It has a dome. That’s not Roman. It’s a Muslim style of architecture.” He explains that an Israeli archeologist had excavated the Roman remains underneath the edifice they are seeing.

The archeologist bypassed the Palestinian narrative by focusing on the subterranean Roman artifacts. To document his point, Aparicio shows Sherman a 1958 photograph of the dwelling with the main road leading to Ramallah. Aparicio underscores, “This is the way to deny Palestinian history here.”

Sherman is at a turning point. He questions, “What if my tree is sitting on the remains of a Palestinian village?” If it is, does the next step entail a question about the “morality” of the Jewish state’s establishment?

The film’s second half moves into a distinctly uncomfortable zone as Sherman conducts a series of interviews, filling in the gaps that the JNF had ignored.

Dr. Uri Davis, co-author of “The Jewish National Fund,” is first on the list. Davis is critical of the organization, qualifying it as Israel’s largest real-estate developer. Registered as a charity in the 1960s and 1970s, JNF enjoys tax-exempt status. Davis doesn’t mince words. “It’s a charity complicit with ethnic cleansing. The JNF is trying to pass themselves off as, ‘We are greening the country.'”

Most of the JNF website outlines “environmental concerns” and beautifying the land. Davis notes, [The JNF] “omits that it hides 1948 to 1949. [Palestinians] were ethnically cleansed from the land and made refugees. The estimated villages destroyed from 1948 are 600. There are 90 villages buried under JNF parks.” He pauses, “KKL-JNF. That’s Zionism.”

Sherman travels to the Negev because he has heard that the “JNF was doing wonderful things.” He meets Haia Noach, the Negev Co-Existence Forum for Civil Equality Executive Director. “Most of Israel doesn’t want to know what happened here before 1948,” she says. Underscoring how the country’s “educational system adds to the lie,” Noah relates wearily, “It’s difficult to challenge it.”

Sherman visits Al-Araqib, originally a village of seventy-five families. The Israeli government has destroyed the community repeatedly, using bulldozers and ruining water wells. Sherman sees ownership papers dating back to 1905, which remain unrecognized by the Israeli government. The only positive note is the Jewish activists who try to remediate circumstances by helping to rebuild.

Sherman was unsuccessful with JNF-Canada, but he got an earful from the fundraiser and former board member of JNF-DC, Seth Morrison, who resigned from his position in 2011. The eviction of Palestinian families in Silwan, East Jerusalem was Morrison’s last straw.

Sherman is left to reflect upon the import of what he has learned. He asks rhetorically, “Now that I knew the truth, what was I going to do about it?”

His subsequent action is to seek Rabbinical input. He reaches out to Miriam Margles of the Danforth Jewish Circle, a congregation that describes itself as “part of a larger progressive Jewish movement.” (Margles is also a co-founder of the organization Encounter.) His top question addresses collective responsibility and what role individual Jews should play in creating repair, or Teshuvah.

Margles supports advocating for justice while recognizing the deep connection to the territory for Palestinians and Jews. She expresses concerns about those who would deny Israel the right to exist, suggesting that it “slides into antisemitism.”

The symbolism of trees in the history of Israel/Palestine reveals much. Facts on the ground show that one set of people was “uprooted” to make way for another. The forests symbolize rebirth and regrowth for Jews while representing destruction for Palestinians. The razing of olive trees is an ongoing strategy of right-wing settlers to terminate Palestinian livelihoods and property ownership.

Sherman’s way into the conundrum was a tree. The documentary’s final scenes show him creating a full circle for himself as a Jew and a filmmaker.

I interviewed Sherman about how Israel factored in his upbringing, delivering a story that innumerable North American Jews have unreservedly accepted.

Regarding his goals for “My Tree,” his answer was simple. “To make Israel accountable for its treatment of the Palestinians and the ongoing occupation. We’ve got to really grapple with it.”

“My Tree” was the opening film for the 2022 Partners for Progressive Israel Symposium. It is available to stream, rent or buy on numerous platforms.

I would love to be wrong. On this issue, however, I have myself to be wrong only infrequently. But so many diaspora Jews who are publicly critical of Israel and the Zionist enterprise are Jews who, for one reason or another, have not carried their Jewishness in the next generation. Does this apply to Jason Sherman?

No.