“Frida Kahlo: Art, Garden, Life”

One might think that as the subject of innumerable books, a Hollywood movie, and status as a feminist and artistic icon, there wouldn’t be anything more to add to the conversation on Frida Kahlo. However, the recently opened exhibit at the New York Botanical Garden entitled, “Frida Kahlo: Art, Garden, Life” is proof to the opposite.

The New York Botanical Garden, located in the Bronx, has previously presented shows that delve into an examination of public figures and their connections to nature and gardens. The subjects were Charles Darwin, Emily Dickinson, and Claude Monet.

With the Kahlo exhibit, visitors not only experience what the staff has termed “an evocation” of the artist’s garden at the Casa Azul (Blue House), they have the opportunity to view artworks by Kahlo that specifically reference her relationship to the natural world.

Over two years in planning, a top-notch team was assembled to bring veracity to a replicated environment. Todd Forrest, Vice President for Horticulture and Living Collections, spoke about efforts to “create a sense of place.” Kahlo’s vegetation imagery was “rendered with botanical specificity,” noted Forrest, who pointed out her “sophisticated understanding of plants.”

Adriana Zavala, Ph.D, was tapped to be the guest curator. Author of Becoming Modern, Becoming Tradition: Women, Gender, and Representation in Mexican Art, Zavala brought a specific sensibility to her focus. Moving away from the drama of Kahlo’s life and loves, her goal was to have attendees see Kahlo through “her plants and house,” and to comprehend her as the “exuberant, deeply intelligent” intellectual that she was. Zavala spoke of Kahlo’s work as being “charming and challenging — reflecting a sharp wit.” Qualifying Kahlo’s home as an “extension of her personal cosmology,” Zavala said, “There are still things to learn about Kahlo.”

Leading several trips to Mexico, Zavala steered the exhibition team to resources needed for immersion in the sphere of all things Kahlo. This included researching archival materials and photographs of the garden at the time it was being developed. Scott Pask, a Broadway design veteran, implemented his digested analysis to formulate the “scenic design” he then staged in the Bronx. One of his stunning contributions was translating the organ cactuses situated at Kahlo’s and Rivera’s home In San Ángel to an “organ cactus wall” abutting the outside of the Courtyard Garden.

Kahlo’s husband, Diego Rivera, is sharply felt in the Casa Azul, specifically in a regeneration of the pyramid that Rivera had built to house his pre-Hispanic collection. This structure is front and center, with each individual step showcasing flowering plants and and a vast array of succulents and cactuses.

The Mexican pots were hand-dyed with tea and coffee to capture the exact hue sought by Francisca Coelho, who designs and installs the major exhibitions in the Conservatory. At the base of the pyramid, are additional specimens.

In the Casa Azul setting, we see Kahlo’s work table with paints, brushes, and books on botany. She regularly pressed flowers and leaves in the pages of her volumes of reading material. It was not surprising to learn that she observed specimens of insects and plants through her father’s microscope.

Another feature of the exhibit is an installation by artist Humberto Spindola. Originated at the Museo Frida Kahlo in 2009, Spindola used the painting, Two Fridas, (1939) a quintessential Kahlo oil on canvas, as the premise for his creation. Building mannequins structured from reeds, hemp, yarn, and wax, and dressing them in acid-free tissue paper colored with special pigments, Spindola incorporates traditional Mexican folk art techniques to fabricate the dresses from the painting. Kahlo’s two outfits, one of European derivation and the other from her mother’s region of Oaxaca, share equal power in the balanced halves of Kahlo’s personal character.

In a performance piece, two male models in wearable versions of the clothing, walked in opposite directions circling the sculpture. The use of men to embody both Fridas operates as a subtle nod to Kahlo’s fluid sexuality.

The daughter of a marriage between a German father and a Mexican mother of Spanish and indigenous descent, Kahlo strongly identified with the melding and fusion of disparate cultures — particularly as they evolved toward a new nationality unity. This concept was encompassed in Kahlo’s work as a manifestation of unified differences: the Mesoamerican and the European, the sexual and the emotional, the life force and the decay of death.

Duality and “hybridity,” as Zavala repeatedly underscored, are primary in Kahlo’s world outlook. With these premises in mind, Zavala made her selection for the paintings and works on paper in the LuEsther T. Mertz Library’s Art Gallery. It is this backstory and the context of Kahlo’s horticultural passions that inform a reading of her fourteen showcased works.

Small Life (II) is an observational watercolor that records organic forms scrutinized by Kahlo. At the time she signed this piece, Kahlo used the German spelling of her first name.

Small Life (II), c.1928

Private Collection Courtesy Galeria Arvil

© 2014 Banco de México Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museums Trust

Mexico, D.F. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

The Preparatory Sketch for Portrait of Luther Burbank is displayed in tandem with the resulting oil painting. Burbank was a horticulturalist who pioneered food development through grafting and cross-breeding. In the drawing, there are literal items referencing Burbank’s work, such as hands planting seeds and wielding a spade. Burbank rises from a tree trunk, while the roots envelop a corpse-like figure. (He was actually buried under a tree in his garden.) The painting is simplified, with greater emphasis on the cycles of growth and decomposition, along with imagery commemorating Burbank’s achievements.

Portrait of Luther Burbank, 1931

Museo Dolores Olmedo, Xochimilco, Mexico

© 2015 Banco de México Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museums Trust

Mexico, D.F. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

The lithograph Frida and the Miscarriage is a diaristic recounting of Kahlo’s angst about her lost pregnancy, imbued with her knowledge of biology that came from her early medical studies. The child that might have been is rendered in totality, down to the male genitalia.

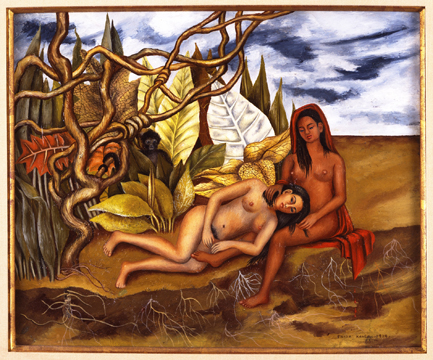

Two Nudes in a Forest is emblematic of the ongoing theme in Kahlo’s pictorial vocabulary of her European and Mexican roots. Set off to the left of the canvas, rather than centered, the sky and the knotted branches have a foreboding aspect. As in other paintings, it is the Mexican figure that is nurturing and giving succor.

Two Nudes in a Forest, 1939

Collection of Jon Shirley

© 2015 Banco de México Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museums Trust

Mexico, D.F. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Securing the widely reproduced Self-Portrait with Thorn Necklace and Hummingbird (which is also the face of all the exhibition’s material), was a major coup. It is always a revelation to see, in person, a work well-known through reproduction. In this contemplative presentation of self, Kahlo brings into the picture plane personal iconography through the use of favored pets and plants. Situating herself in front of a curtain of huge elephant ear leaves with various veined patterns, Kahlo places an animal at each shoulder. The monkey appears almost childlike. It is engaged in its own thought process, while examining Kahlo’s necklace — which recalls Christ’s crown of thorns. The black cat, in a stalking position reminiscent of a leopard about to pounce, is watchful and protective. Despite the allusion to pain and mortality that radiates from the lower two-thirds of the painting (including the inert hummingbird), the delicately rendered butterfly pins in Kahlo’s hair and the fused winged insects and flowers suggest hope. Their palette tonalities tie in with Kahlo’s shirt, as well as the lone white leaf behind Kahlo’s head — speaking to her unique individuality.

Self-Portrait with Thorn Necklace and Hummingbird, 1940

Harry Ransom Center, The University of Texas at Austin

© 2014 Banco de México Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museums Trust

Mexico, D.F. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

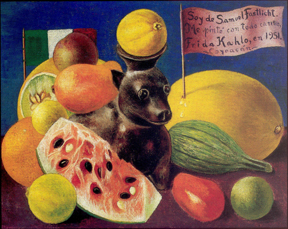

A group of still life paintings from 1951-1953, the last years of Kahlo’s life, are intense studies of fruits and vegetables that emphasize seeds, ripeness, sexuality, and fecundity. Inserted are totems and objects from Mexican culture from a miniature flag to Kahlo’s favored hairless dog, the xoloitzcuintle, rendered here as a piece of pottery. Despite her failing health, Kahlo was firmly entrenched in capturing the vitality of life.

Still Life (For Samuel Fastlicht), 1951

Private Collection, Courtesy of Caleria Arvil, Mexico

© 2015 Banco de México Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museums Trust

Mexico, D.F. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

The New York Botanical Garden has supplemented the exhibition with programmed activities — music, dance, film, poetry, and lectures. There is a top-notch catalogue (Included are photographs and information on relevant plants, with the American and Mexican names as well as the Latin nomenclature.) and a mobile guide. All labels are in English and Spanish.

The museum has projected that 300,000 visitors will experience the exhibit. With the riches to be discovered, that may prove to be a low estimate.

Frida Kahlo: Art, Garden, Life

New York Botanical Garden

Through November 1, 2015

Marcia:

It was wonderful to meet you yesterday. Thanks so much for coming to hear me speak at Wave Hill.

I have thoroughly enjoyed reading this article, and seeing “Small Life” which I have never seen before. I look forward to exploring much more of your site, and to visiting the NYBG to see this show.

All the best,

Anne