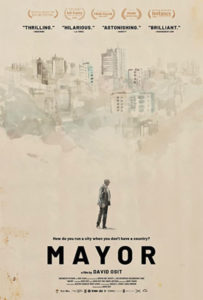

“Mayor” – A View from Ramallah

For most American Jews, the occupied Palestinian territories exist as an abstraction. Their towns are names that are heard on the news, often in a negative context.

For most American Jews, the occupied Palestinian territories exist as an abstraction. Their towns are names that are heard on the news, often in a negative context.

Director David Osit shifts that narrative in his new documentary “Mayor.” Osit follows the daily schedule of Musa Hadid, who presides over Ramallah with intention and devotion that earns him hearty welcomes from citizens. He is a constant presence on the streets of his metropolis.

In opening shots, Osit’s camera pans the streets of Ramallah, accompanied by a swelling musical score and urban imagery equivalent to a Woody Allen ode to Manhattan. Humor is integral to Osit’s approach, although occurrences facing the residents are anything but funny. Hadid’s engaging personality gives Osit the perfect interlocutor for his story. It’s easy to imagine Hadid as a modern-day Fiorella LaGuardia, the kind of a guy who would read the Sunday funnies to kids if it was called for.

Ramallah, a historically Christian city, serves as the seat of the Palestinian government. It is at the epicenter of Palestinian commerce and culture. It is also ringed by Israeli settlements.

Storefronts of various establishments, from the Café de la Paix to Popeyes, are shown. Coca-Cola ads pop up alongside meticulously landscaped areas. The sound of church bells and the call of muezzin are accompanied by the visual juxtaposition of a cross and a minaret.

The key event connecting the various story threads concerns detailed plans for the annual Christmas celebration, including an outdoor concert, a tree lighting, the arrival of Santas, a parade, and a children’s activity. (There is a Plan B if it rains.)

During the time period when Osit worked on the film, several important events occurred. These are interwoven throughout, via news from the television or directly in conversations. When told that Trump will announce Jerusalem as the capital of Israel and the American embassy is being moved from Tel Aviv, Hadid comments, “We’re doomed.”

Meetings between the Mayor and staff members occur outside, in his car, and at Ramallah’s City Hall, established in 1908. Ongoing dialogues include how the city should be branded (Hadid is more concerned with infrastructure.), new doors needed for an elementary school, beautifying the old town with benches, and the daily humiliations from Israeli rule. “We are living under an occupation with hardly any help from the outside, and no sources of income,”Hadid underscores.

Yet, despite the ongoing ordeals, Hadid keeps his eye on whatever ball he is juggling. When he visits a class of third graders to check out the “door situation,” he stays focused on the task at hand – even as a radio blares the news that “the Israeli army has arrested seven citizens across the West Bank.”

Hadid comes from one of the five founding Christian families of Ramallah. His dedication to the city is palpable. His goal is to be a “pragmatic leader.” Hadid understands the situation that he and his city are trapped in. Coming from a background in civil engineering, municipal services – rather than political statements – are his priority.

When the Israelis close off the entrance to Ramallah, raw sewage begins to fill the streets. Hadid has the pavement immediately washed down. Dealing with the ramifications of settlers polluting Palestinian irrigation water and burning olive trees are all part of a day’s work. However, Hadid does not shy away from speaking about facts on the ground. In response to a dumpster fire of burning tires, he states wearily, “We need permanent solutions.”

Despite the constant pressures, the tree lighting ceremony holds Hadid’s full attention. His philosophy is clear: “Remember to make space for joy until we get freedom and independence.” Hadid leads his constituents in their national anthem and then asks for a moment of silence for the dead. Simultaneously, he takes notice of two unlit bulbs.

Ramallah, like other cities, hosts delegations from foreign countries. Speaking with a group of German parliamentarians, Hadid points out the problems of being a mayor on occupied land. He explains that in 2002, Israelis invaded Area A and demolished the city’s infrastructure. An assistant emphasizes that it has taken fifteen years to get permission for a cemetery to get built. “It’s not nuclear weapons. It’s a cemetery,” he adds dryly. (Osit continually uses humor to highlight the negatives.) To German suggestions of personal exchanges between Palestinians and Israelis on a local level, Hadid stresses, “It’s about dignity, which is not negotiable.”

The audience does get to see an Israeli and Palestinian interaction, and it’s devastating. After the embassy move, there are Israeli incursions into the West Bank, including Ramallah. This results in the invasive presence of soldiers in the town square, as they approach City Hall. At 7 in the evening, shots are fired. An arrest is made, tear gas canisters explode, and smoke fills the night sky. Israeli soldiers take selfies in front of the Christmas tree, oblivious to the pain they are causing. In response, Palestinian rock-throwing begins as they retreat.

In a quiet voice, Hadid asks Osit, “David, do you think people in America know or hear about what’s happening here?” He then answers his own question with the assertion, “People don’t know about us.”

In a featured panel at the 2020 OtherIsrael virtual film festival, Osit spoke about his efforts to show Ramallah through the eyes of its citizens and Hadid; working to balance the tragic with the comic. In expressing his motivation behind the film, Osit stated, “I always understood Judaism to be deeply rooted in human rights.”

An end credit dedicates “Mayor” to the memory of Palestinian filmmaker and journalist Yaser Murtaja (1987-2018).